Are Interceptor Drones Worth the Hype?

The Dronewall, Part 2: The Hits & Misses, Past and Future of the Field of Interceptor Drones for EU & NATO Nations

“It is now critically important to develop alternative systems to counter the Iranian Shahed drones. We have great cases with the Army of Drones when not only foreign drones but also domestically produced UAVs were supplied to the front line. The same should be implemented with the development of Ukrainian sky protection systems,”

— Mykhailo Fedorov, Deputy Prime Minister for Innovation, Education, Science, and Technology, Minister for Digital Transformation.

"If we are being attacked by a swarm of drones, we need a swarm of counter-drones."

— Karl Rosander, CEO, Nordic Air Defense

How many types of interceptor drones do you know? Two? Three? I bet there are more in this article than any number you come up with…

Interceptor drones are still a pretty young segment of the air defense market, but many argue that they’re already coming of age. So, in this article, we’re going to take a look at the different technological approaches, suppliers and models, their claims and any available evidence, and gain an understanding of where the interceptor drone market truly stands at the end of 2025, whether they might even be absolutely necessary to defend against Shahed-like long-range drones, and whether it looks like they’re here to stay or just a temporary fix. Most crucially, though, the discovery laid out in this article will prove exceptionally informative for those of us (author included), which are looking to design systems, structures, processes and incentives that allow us to build the next set of crucial innovations. Because the enemy doesn’t sleep, and the threat profile is evolving rapidly, which is why - as I will prove further down in the article - NATO’s and the EU’s chasing of yesteryear’s drone innovations from Ukraine makes very little sense. As a matter of fact, it might be that at the end of the article, we’ll find that it makes little sense to procure interceptor drones at all, despite them working well, and that there’s another solution that far outpaces that of the current shopping frenzy for interceptors. Might. Read on to find out.

Let’s talk about interceptor drones. Welcome to the Dronewall Series, Part 2: Are Interceptor Drones Worth the Hype? The Hits & Misses, Past and Future of the Field of Interceptor Drones for EU & NATO Nations

By the way, since we’ve covered a lot of the bases around drone technology, AI, computer vision and autonomy in past Deep Dives, I won’t repeat those here, in order to keep my promise of optimizing for slightly more crisp Deep Dives.

With a big thank you for your continued support as always, let’s get to it!

But first, as always, let’s start with some context.

What You Will Learn in this Article

Creativity Loves Constraints: the Emergence of Interceptor Drones

Why Are NATO Nations Purchasing Interceptor Drones?

Which Types of Interceptor Drones Exist? What’s On the Market at the End of 2025? How Autonomous Are They? More than ten different interceptor drone styles detailed!

Are Interceptor Drones Filling a Competitive Niche or Are they Just a Placeholder? Five Reasons for Skepticism, Nine Reasons Why Interceptor Drones Are Looking Like a Winner.

Summary, Conclusion and Recommendations for MoDs, Investors and Industry

Hello. Thank you for supporting my work. I provide technical knowledge and market intelligence about unmanned systems and AI for governments, OEMs and investors.

TECH WARS features comprehensive deep dives full of primary research, intelligence and experience I gather myself, from the offices of OEMs and startups to the forward edge of innovation.

They’re being read by MoDs, OEMs and SMEs, as well as their investors in PE, VC and banking. The TECH WARS Deep Dives take roughly a month to research and write (zero AI), are published bi-weekly, and are supported by my subscribers. A subscription also gives you access to hundreds of pages of already released TECH WARS Deep Dives. Go ahead and give it a try - you can cancel risk-free anytime!

Creativity Loves Constraints: the Emergence of Interceptor Drones

Interceptor drones, like most of the novel defense technologies of the Russo-Ukrainian war, emerged in Ukraine due to a shortage. Western nations didn’t supply sufficient air defense munitions to address the sheer amount, and later the evolving threat profile of Shahed-136 (Geran 2) and Shahed-238 (Geran 3) and their siblings. Understanding this element is going to prove crucial later. Due to their extensive experience with FPV drones, and the industrial base which had already been supplying tons of imports and domestic production of drones and drone parts, Ukrainian commanders, politicians and industry realized that drones might be the solution yet again. To be more precise, it was at the second Ministry of Digital Transformation’s “Anti-Shahed” hackathon in June 2023, which ran off of the Ukrainian government’s delcaration that it wants an “Army of Robots” (an actual doctrinal program), where the idea of interceptor drones in their contremporary shape was born. Contrary to what has been suggested in the media, these drones didn’t emerge from random tinkering. This was a deliberate and coordinated effort. See the quote above.

It was at this hackathon, where teams from the armed forces and commercial engineers and business people collaborated on hacking solutions to counter Shahed drones without Western missiles. Three winning teams were selected out of a total of 50-60 applicants, and have received $1 million in prize money (Big learning about Ukrainian defense innovation incentivization and stimuli: When was the last time you’ve heard a European hackathon with that size of a carrot? Exactly). Luckily for us, some images have been shared in the open source. Let’s take a look at some of the solutions which were developed back then; they’re quite informative:

Photos: Mykhailo Fedorov, Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine

What do you see here? I see variety. I see crude development, I see three different approaches which have all found their refined future expression after coccooning and metamorphosizing within the nourishing ecosystem that currently only exists in one country, Ukraine. Let’s take a look a the first drone. That’s not a bullet-shaped racer drone. That’s a drone that emerged from the design of a quadcopter and was re-imagined for rapid and stable flight (look at that slender but long fuselage; can you imagine the size of the battery pack?) towards or through a kill-box, and then to horizontally chase and home in on a target and hit it. The later adoption of bullet-shaped racer drone designs might have never happened if it weren’t for this kind of crude design at the start of the evolution. It is way longer than racers, it features stabilizing fins, it still features a pull-prop configuration, while most racers (and most ground-launched interceptor drones) today feature push-prop configurations (the propellers pointing “backward” instead of “forward”, which influences the airflow and handling/control). The drone also appears to be mounted on a kind of rail - hinting at the idea of either potential ramp launch (though interestingly bottom-mounted instead of mostly top-mounted versions today) or hard-point fastening similar to the current, widely propagated use case of mothership drones (detailed below) with chaser FPV drones mounted underneath their wings (in order to get them to altitude). While potentially partially inspired by racer drones, I’d claim that there’s more to this than for this drone concept to have emerged simply by itself because of people looking into racers.

Racers have evolved to become more and more drop-shaped. Photo: Core77

Let’s take a look at the second drone image. This is a very different design, yet one which has established itself firmly today (with alterations). It’s a design built for ground-based launch, usually nowadays off of rails/ramps, and often equipped with a jet engine. This isn’t made to counter (just) the relatively slow, 180-km/h, Shahed-136, but seems built to chase a Shahed-238, which flies at more than 500 km/h. The impression is likely deceiving, though: the 238 was first shot down in Ukraine (and documented in the open source, meaning on Telegram) on January 8, 2024. More likely, this is “just” a different approach, which prioritizes speed and agility over cost and similarity to the existing quadcopter designs. The same seems true for the third design, which clearly emphasizes flight time with its light-weight, large-wing setup. Being able to loiter in a designated airspace for longer and fly further towards a target provide clear advantages in a country where radars are in short supply, and this concept showcases a potential solution to those kinds of self-assigned problems.

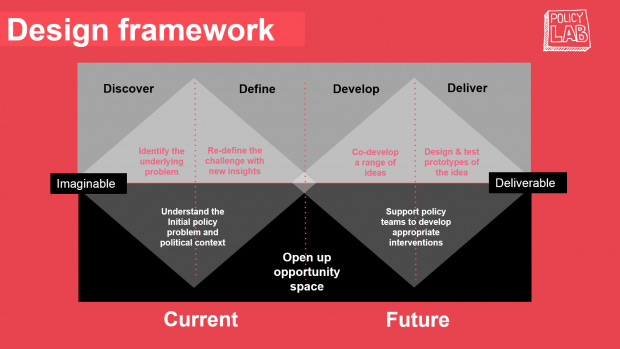

This is the magic of hackathon-style types of environments: they encourage the “Double Diamond” style of research and development. The Double Diamond describes a design framework which is used in most creative design processes, and in which you start by diverging towards as many ideas as possible, then converge towards the best solutions in a structured approach. You do that both for the identification and description of the problem(s) you want to address and the solutions. this way, you ensure that you 1) don’t miss any problem definitions, and 2) potential solutions. If you’re interested in this approach to problem-solving, I’m actually trained in Design Thinking at Stanford and Design Sprints at Google (as Google Ventures transformed this methodology into a concise format), and will include a link to the website of the UK Design Council. I’ve seen these methods work for anything from services to space hardware, countless of times.

The Double Diamond, widely in use in innovation, was first conceived by the UK Design Council more than 20 years ago. Image: UK government

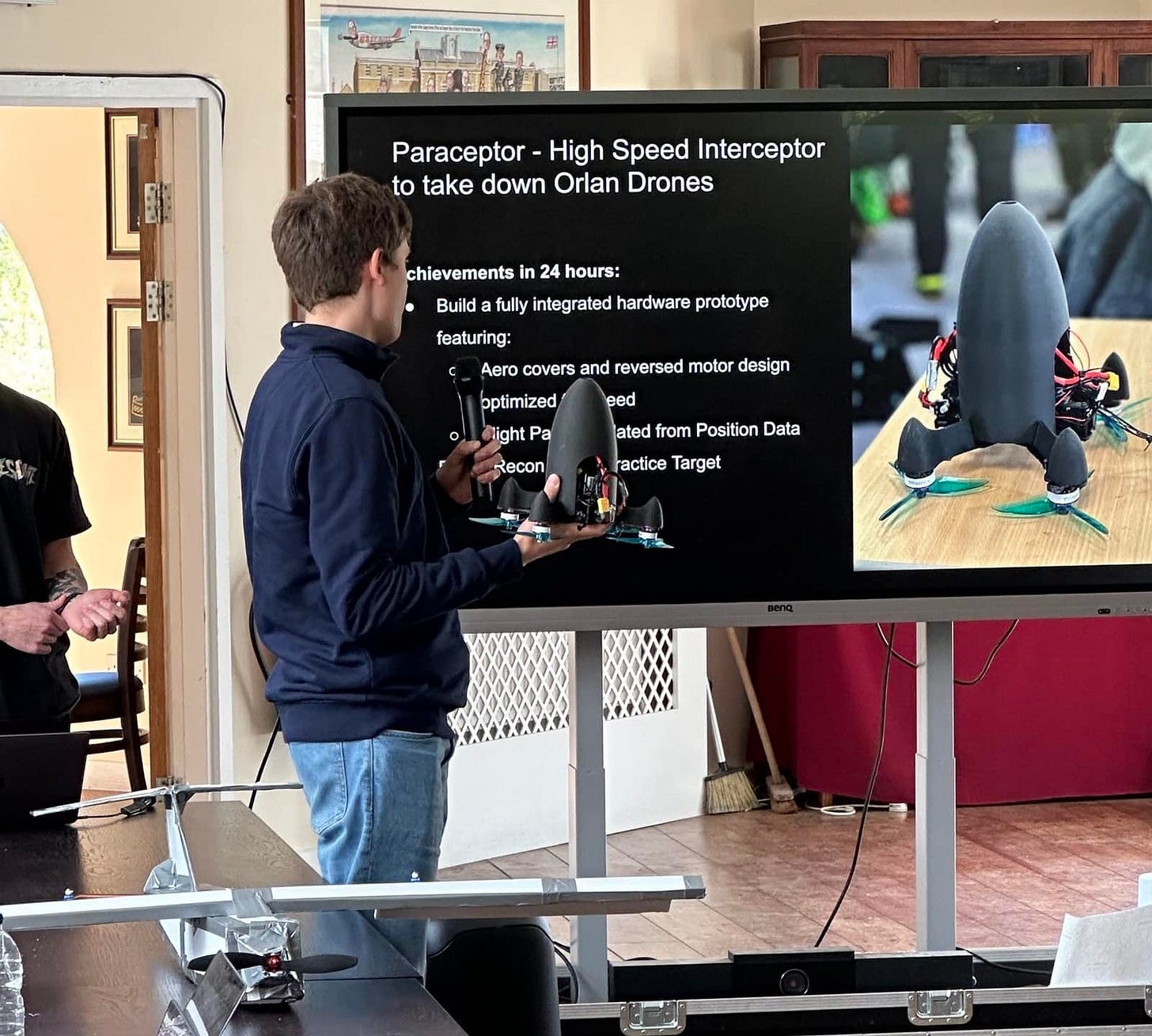

But I digress. Back to the evolution of interceptor drones. The next publicly visible development (the webpage has since been taken down) occurred at the DoneXL Defense Tech Hackathon in April 2024. It saw the development of the Paraceptor drone, which was designed specifically for taking down Lancet drones. ZALA Lancets are shorter-range, faster, tactical strike drones, which are most commonly used on or near the battlefield. It features a more aerodynamic but stubby shape, and already proposes automated flight path calculations - a step towards low-level autonomy.

The Paraceptor and its prey, the ZALA Lancet. Photos: DoneXL, Wikipedia.

Parallel developments took place. It’s not publicly known when the Wild Hornets, a Ukrainian miltech company/non-profit volunteer organization (which are essential drivers of the Ukrainian innovation machine), first developed the now famous Sting interceptor drone, but its relatively crude, 3D-printed initial public appearances in October 2024 suggest that the now widely used FPV drone started development relatively early; likely around late 2023, or early 2024. The first photo of the Sting from October 2024 also reveals something crucial about interceptor drones. Take a look:

A sting doesn’t need to be large to hurt. First published photo of a Sting interceptor. Photo: wild Hornets Telegram Channel

Interceptor drones are arguable the most compact solution to Shahed-sized aerial threat profiles ever invented. This has implications on logistics, and their often 3D-printed fuselage, as well as their commercially-sourced parts have implications on cost and supply. This is part of why NATO nations are interested in them. But other reasons exist.

Why Are NATO Nations Purchasing Interceptor Drones?

This is a complicated question, because there are lots of factors that flow into this. Let’s start with the obvious one: FOMO. Interceptor drones are novel, and sexy. The look cool, the footage produced with them looks cool (and falsely suggests autonomy and 100% successful intercept rates), and the pilots piloting them look cool with their headsets. Every procurement manager, every military planner these days is fully aware that they have to have drones in their high-low mix in order to stay credible and at the top of the conversation. The discussion whether drones themselves are here to stay is definitely over, and the answer is crystal-clear, and the ongoing ramp-up of the procurement of ISR and strike drones is easing the decision to expand into other categories. There’s also an overlapping answer to this question across the Ukrainian and NATO governments: the missile gap is real. The combined West doesn’t have enough missiles to counter aerial attacks, and isn’t capable of producing enough of them in the near-term to match Russia and/or China, by a stretch. There are a couple more less intuitive responses to the question why NATO nations are purchasing interceptor drones, and newly emerging alternatives, but we’ll park those for the moment, and first dedicate ourselves to a question which needs to be clarified beforehand:

Which Types of Interceptor Drones Exist? What’s On the Market at the End of 2025? How Autonomous Are They?

Alright, let’s get to the meat of the article. This part will consist of a list of available systems and their specs, a description of the different categories and their significant features and differences and an elaboration about the state of autonomy. For clarification, for obvious reasons, I am not going to discuss systems of suppliers which I am currently scouting or evaluating for governmental programs or investors, or those by teams, Ukrainian or other, that have shown their unannounced system to me in confidentiality, or systems that are in use in Ukraine but not yet publicly announced. I’m sure that’s understood.

What you see is what you get: more than 6k words, or 30 pages, of dense, up-to-the-minute intel.